A WONDERFUL DETECTIVE STORY

The Fatal Chord,

or the Baffling Mystery of the Carnegie Hall Murder.

By Albert Payson Terhune.

To Be Completed in Twelve Dally Instalments.

SYNOPSIS OF PRECEDING CHAPTERS

Cyril Ballard, a young New Yorker, is killed during a musicale at Paul Craddock’s apartments in Carnegie Hall. Several apparently supernatural events attend his death. Poison tablets, also, are found in his pocket, but the autopsy reveals no trace of poison in his system. As Gresham and Beckwith, two detectives, are discussing the affair, they are joined by a tall, thin Englishman, whom Beckwith introduces to Gresham as the “ideal detective.” To which Gresham replies: “Do you mean to tell me this is SHERLOCK HOLMES?”

This other makes an evasive reply and tells Gresham that the latter may refer to him merely as “The Englishman.” The Englishman undertakes to solve the Ballard mystery.

The Englishman's suspicions at length fall on Royce Ballard, the murdered man's brother. He has reason to believe that Royce carries a certain document bearing on the crime, and resolves to secure it.

He fails in his first attempt.

CHAPTER VII.

A New Plan

Gresham and Beckwith sat smoking and taking desultory drinks from long glasses beside a pillar in the Hoffman House café.

“What’s happened to The Englishman, I wonder?” observed Beckwith for the tenth time. “He promised to be here by 6.30. It’s nearly 7.”

“When he does come,” said Gresham, “you may be sure he’ll bring with him what he went for. That fellow simply can’t lose. I’ll bet you $10 even that he got away with the goods, made the arrest, had Ballard searched, found what he wanted and cleared out.”

“I’ll take that bet,” announced Beckwith, after a moment’s reflection. “I’ve no doubt you’ll win, but a wager will help change the tedium of waiting into something like suspense. You should have seen his make-up. It was great. He’ll probably have it on when he comes here.”

“I wish you’d lay your cards on the table,” growled Gresham fretfully.

“What do you mean?”

“Why, you know whether this Englishman is really Sherlock Holmes or if he is the original from which the character of Sherlock Holmes was drawn. If he really is Sherlock Holmes, why should he be so stubborn as to refuse to say so? If he isn’t what could possibly be the game in letting believe that he is?”

“I’m afraid I can’t help you out,” said Beckwith, “I –“

“Then I stick to my belief that he is really Sherlock Holmes and that he hides his identity in order to avoid notoriety. Isn’t that so?”

“In his own good time he’ll doubtless explain everything clearly. In the meantime I suppose I must keep on calling him The Englishman, and – hello, there he comes.”

The Englishman - not the square-jawed Central Office man, nor the elderly rustic - sauntered in, nodded curtly to the two and sat down.

Beckwith saw at a glance that something was amiss - something serious enough to ruffle the gigantic composure of even a man of The Englishman’s self-control.

Gresham, denser and less tactful, asked, “What luck old man?”

“None,” snapped The Englishman. “Get me a scotch highball, waiter.”

“None?” echoed Gresham, amazed. “No luck at all? I thought you never failed.”

“Did you?” observed The Englishman coldly. “Well, you know better now.”

“Didn’t even” –

“Oh, don’t rub it in, Gresham,” interposed Beckwith. “He’ll tell us about it in his own time. If he missed seeing Ballard to-day, he’ll catch him by the same trick to-morrow.”

“I saw him,” said The Englishman, somewhat less reluctantly and speaking fast as though to be quit of some unpleasant duty. “I saw him at a place to which I had induced him to come. I served the warrant and” –

“Where was this place?” interrupted Gresham.

“Pennsylvania Station” –

“Jersey City!” cried both detectives in surprise.

The Englishman nodded.

“Why, man,” exclaimed Gresham, “A New York warrant is no” –

“No use in Jersey City,” finished The Englishman. “Yes, my friend, I know that quite well. In fact the knowledge has been pretty thoroughly instilled into me this afternoon. It comes late, but it’s very effective now that I’ve acquired it. I’m not likely to forget. If I’d known a bit earlier” –

But,” suggested Beckwith, “why didn’t you tell us where you were going to meet him? We could” –

“Because I was a fool, I suppose,” replied The Englishman.

“Think of the greatest detective on earth talking like that!” muttered Gresham, dumfounded at the downfall of his hero. “Now” –

Beckwith kicked him furtively and the Central Office man subsided.

The Englishman recounted tersely yet vividly his experience of the afternoon. As he did so the gloomy disgust on Gresham’s face gradually cleared away, and, as The Englishman reached the point in his recital where he described the way in which, as the pseudo countryman, he had joked the baffled bluecoat, the old look of admiration re-dawned in Gresham’s eyes.

“Gee!” he cried. “You’re great, all right, even if you are a little shy on interstate criminal law. And now, what are you going to do?”

“Do? I’m going to do what I set out to. To get this precious packet or whatever it is that Royce Ballard carries in his breast pocket. The thing that Bona Pittani hinted contained the secret of Cyril Ballard’s murder.”

“But that warrant trick won’t work twice. The man’ll be on his guard.”

“Of course he will. This time I’ll take no chances of falling foul of your queer Yankee criminal laws. My experience has been that, though laws differ in every country, yet criminals of all nations are practically the same. Good! Then I’ll be a criminal, a highwayman, a hold-up as you Americans call it. I intend to hold up Mr. Royce Ballard and rob him of this treasure.”

“In Jersey City?” laughed Beckwith.

“No, in Reade street, New York.”

“Reade street? Why, Reade street’s in the busiest section of the city. It’s crowded.

What are you thinking of?”

“I admit it is crowded in the daytime and I have no intention of luring Ballard into a crowd and asking him to stand and deliver. There are two places on earth which are, to me, the acme of deserted desolation. One is the centre of the Sahara. The other is a downtown New York street after business hours.”

“Oh, you mean to get him to Reade street at night and hold him up. But won’t he be a little coy about taking the bait after a lesson like this afternoon’s. He’s” –

“You people might give me credit for a little intelligence in spite of my blunder to-day,” complained The Englishman. “Kindly listen to the outline of my plan and see if it strikes you as foolish. It is daring, I admit. But, with a little skill, there is no reason why it should not succeed.”

“We’re listening,” said Gresham more respectfully.

“I’ve had my eye on Mr. Royce Ballard for some time. In a Reade street office building less than a block west of Broadway he has hired a room which he’s fitted out as a laboratory.”

“Laboratory? I remember, chemistry was the one study he cared for at the medical school. That’s where he made those poison tablets and” –

“Yes, if he made them and if they were poison. He keeps the laboratory locked. Even the janitor can’t get in. He hires the room under a false name. He goes there two or three afternoons a week, and stays (Presumably working over his experiments) sometimes till 10 or 11 o’clock at night. I’ve been watching him, you see.”

“But how can you tell when he is to be there?”

“He is most scrupulous in the matter of dress. On the afternoon he is going to his laboratory he doesn’t get into frock coat and topper, but wears business clothes. To attract less attention in the business district, I fancy. Well, his valet has undertaken to send me a telegram, on the quiet, the next afternoon he wears a business suit. I shall be waiting for him at the door of his office, taking care there is no policeman near. The rest should be easy.”

“Do you know,” remarked Beckwith, “There is something utterly uncanny and unnatural about all this case. First, Cyril Ballard’s sudden death, the moment of darkness and the chord of music from the piano. Then this mysterious ‘something’ that Royce Ballard carries always in his breast pocket and which connects him to the crime. What can it be? Than the fact that no trace of any known poison was found in Cyril’s body. It baffles me.”

“The key of it all seems to be the packet, whatever it is, that Royce guards so zealously,” said The Englishman, “unless” –

“Still thinking of that improbable first theory of yours which you refuse to tell us?” asked Beckwith as The Englishman paused.

“Yes. But that is all so improbable. I’ll send you men word the day I am to try my hold-up experiment on Mr. Royce Ballard. Then you can come to my rooms and wait there for me till I return, if you like, and hear my report. I think I can promise you that I won’t return empty-handed again.”

* * * * *

The Englishman had not greatly exaggerated when he described the downtown business district of Manhattan as the most desolate spot on earth after business hours. And so it appeared to him as he strolled southward along lower Broadway on this night following his Jersey City experience.

The streets leading to the ferries still contained a few hurrying figures. Broadway, so thronged in daylight hours, was nearly empty; the nearly vacant yellow cars whizzing along at greater intervals and at far greater speed than would have been permissible before dark. City Hall Square contained the usual quota of life’s failures huddled on its shabby benches; while across on Park Row traffic was still fairly lively.

But most of the side streets stretched away, silent, empty and dead as the Tombs of Luxor. The tread of stray policeman or belated worker awoke weird echoes from the high, forbidding fronts of silent buildings; the electric lights seemed to intensify rather than to dissipate the gloomy desolation of it all.

Turning west from Broadway, The Englishman strolled leisurely through Reade street.

A light twinkled in a single window on the fifth floor of a building half a block down the street. There Ballard was still at work. Glancing about to see that no policeman or watchman was visible, The Englishman hurriedly tried the door leading to the upper floors. It was locked. He dared not risk exposure so early in the evening by picking the lock, so he slipped into the protecting angle of a wide first-floor sign and waited.

Hour after hour passed, and the district grew even emptier and more silent.

“He’s working late to-night,” commented The Englishman as midnight struck from a distant bell. “It should be safe to try to break the lock now. I’d rather take my chances upstairs alone with him in his own laboratory than in the street where a half dozen of these lynx-eyed American police may drop down on us at any moment.”

He stepped forth from his hiding place.

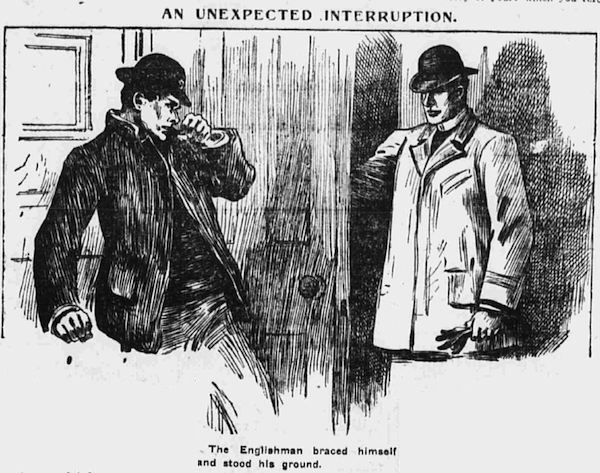

A shrewd eye would have been needed to detect the dapper English detective or the Central Office man of the old countryman in the grim-faced, shabbily-dressed thug who stood revealed by the glow from a far-off electric light. Not so clearly a tough character as to attract notice, there was nevertheless an ill-groomed, unshaven air about the man in the new disguise which would divert any suspicion from the theory that the proposed attack was not a mere mercenary hold-up perpetrated by a professional.

Another glance up and down the street.

“What can have happened to Ballard to keep him there so late?” muttered The Englishman as he bent to the task of picking the lock. “He never worked so late before. Can anything be the matter?”

As he was applying an odd-shaped steel instrument to the lock, he suddenly leaned back. But he was too late to escape notice.

Even as The Englishman sought to retreat, the door he had been assailing was flung wide open.

The Englishman braced himself for the contingency and stood his ground.